By the end of the month, two Alabama hospitals will stop delivering babies. A third will follow suit a few weeks later.

That will leave two counties — Shelby and Monroe — without any birthing hospitals, and strip a predominantly Black neighborhood in Birmingham of a sought-after maternity unit.

After that, pregnant women in Shelby County will have to travel at least 17 miles farther to reach a hospital with an OB-GYN. And because the county, one of Alabama’s largest, is bordered by another whose hospital also lacks an obstetrics unit, some of those residents are also losing the closest place they could go to deliver their babies.

“There’s a sense of dread knowing that there’s going to be families who are now not only driving to the county over, but driving through three counties,” said Honour McDaniel, director of maternal and infant health initiatives for the March of Dimes in Alabama.

People in Monroe County, meanwhile, could face drives between 35 to 100 miles to a labor and delivery department.

Trekking that far to give birth is not unheard of in Alabama, in which more than a third of the counties are maternity care deserts, according to the March of Dimes — meaning they have no hospital with obstetrics care, birth centers, OB-GYNs or certified nurse midwives.The state has one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the country; only three others had higher rates between 2018 and 2021, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alabama also had the nation’s third-highest infant mortality rate in 2021, the latest data available.

Physicians currently or formerly affiliated with the Alabama maternity units about to close fear the consequences for pregnant women and babies, especially if people are not able to reach birthing hospitals quickly enough in emergencies.

“People are going to show up delivering in the ER, and you’re going to have bad outcomes,” said Dr. Jesanna Cooper, an OB-GYN who formerly worked at Princeton Baptist Medical Center, the Birmingham hospital closing its maternity services. “If you show up with a very premature baby and deliver in the ER, and you don’t have a NICU and you don’t have an obstetrics team, things aren’t going to go well.”

The closures come as the need for obstetrics care in Alabama is anticipated to rise as a result of its abortion laws. The state has banned almost all abortions since June 2022.

‘There’s something broken’

The hospitals losing obstetrics departments in Birmingham and Shelby County are both part of Brookwood Baptist Health, a health care network with five hospitals in Alabama. A spokesperson for the network declined NBC News’ request for an interview but said in a statement that the decision came “after careful consideration.”

“We will support a smooth transition of care for patients and Brookwood Baptist Health remains committed to providing outstanding maternity care within our network,” the statement said.

Monroe County Hospital, meanwhile, attributed the closure of its labor and delivery unit to a staffing shortage. The department has just one physician, and at least two are needed to keep labor and delivery services running.

“It seems no amount of money provided by the hospital board for the support of Labor and Delivery has been sufficient to maintain this service. We have supported, and would continue to support, Labor and Delivery if there was someone who could provide the service,” the hospital said in a statement.

In some cases, keeping maternity units open is a financial challenge, since the departments aren’t always profitable, several Alabama physicians said. Around 9% of the state’s residents have no health insurance, according to a report from the Census Bureau, and almost half of the births in Alabama are covered by Medicaid. Reimbursements for that program can be substantially lower than for private insurance plans.

“Nobody wants women and children to do poorly, but you also can’t lose money year over year on a service line,” said Dr. John Waits, CEO of the nonprofit Cahaba Medical Care, which runs medical clinics that take patients regardless of their ability to pay. Several of Cahaba’s physicians deliver babies at Princeton Baptist and Shelby Baptist.

“There’s something broken about the funding stream that helps us take care of our women and children,” Waits said.

Such challenges are not isolated to Alabama. Nationally, fewer than half of rural hospitals have labor and delivery services, according to the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, a policy-focused nonprofit.

And so far this year, obstetrics departments have also closed in California, Idaho, Massachusetts and Tennessee.

The stakes of losing these services are high. A 2018 study found that rural counties that lost obstetric services reported more preterm births within the following year than those that maintained such care. Preterm birth is associated with low birth weight, which was the second leading cause of infant death in 2021, according to the CDC.

Dr. Rowell Ashford, an OB-GYN with Cahaba who practices at Princeton and Shelby, said that living far from a hospital with obstetrics care can discourage patients from getting health issues checked out.

“If patients have blood pressure issues that they’re not tending to because they don’t want to be bothered with the extra 45-minute drive to go be evaluated, then there’ll be times where patients truly have life-threatening issues, but due to the distance and difficulty in getting to the hospital, they may choose not to be evaluated,” he said. “That just feeds into the problem relating to neonatal morbidity and mortality and maternal morbidity and mortality.”

A long drive might also deter some people from going to the hospital early in labor, Ashford added, which could lead babies to be born en route.

‘People were coming there because of how well they were treated.’

Although Princeton Baptist isn’t the only place to go to deliver a baby in Birmingham, its unique approach has gained a reputation. The hospital — located in an area in which 40% of the residents live in poverty — welcomes doulas, boasts a diverse obstetrics team, has staff specially trained to support moms in breastfeeding and provides water tubs to patients in labor. It also had the lowest cesarean section rate in Jefferson County as of 2020.

Dr. Heather Skanes, an OB-GYN at Princeton, said that some of her patients have traveled there from as far as Selma.

“We didn’t have a fancy unit. We didn’t have anything really fancy about the hospital,” she said. “People were coming there because of how well they were treated.”

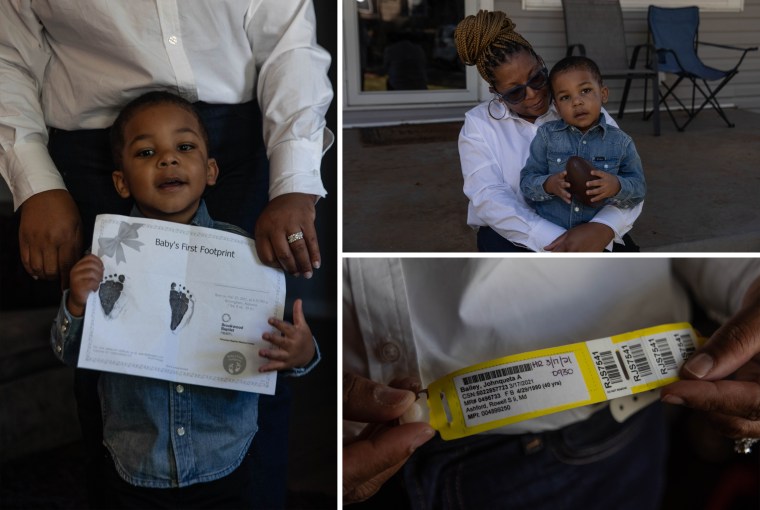

JohnQueta Bailey Archie, 43, delivered her son, Jayce, at Princeton in 2021, under the care of Ashford. It had been almost 20 years since she’d given birth to her older son, and her second pregnancy was high-risk, because she had developed blood clots and fibroids. Plus, as a Black woman, she was aware of the racial disparities in maternal and infant health outcomes.

At Princeton, she said, “I felt like I was heard, I was seen.”

Ahna Frye, 32, has delivered two babies at Princeton: her older son, Holland, in 2020, and another son, Hutton, in May.

During her first pregnancy, she said, she had hoped to give birth at home but went to Princeton on her midwife’s advice after learning that her blood pressure had climbed dangerously high. Skanes eventually delivered Holland via C-section, but Frye said she never felt rushed into surgery.

Frye, a resident of Shelby County, said she chose Princeton because the hospital respected her birth plan. But she knew that if anything went wrong — and it could have, given her risk of pre-eclampsia — Shelby Baptist was right nearby.

If she gets pregnant again, neither option will be available.

“For our family personally, we’re not done having kids,” Frye said. But she doesn’t want to do that without a place like Princeton, she added, and also knows that the distance she’d have to drive in an emergency is about to jump from 10 to 35 minutes.

“That’s the difference in life and death,” she said.